- Screen Colours:

- Normal

- Black & Yellow

For regular readers, you will recognize that this is my first ‘real’ entry since April this year, but in terms of History Society talk summaries, it is the first since June 2020 – an unconscionable time all down to Covid. Happily your History Society is now back, but sadly only for double vaccinated existing members, and then only with limited numbers allowed to attend each month. Trustees will revisit this situation early next year, once hopefully third Covid jabs and Flu jabs have been successfully administered.

I hope that readers who could not attend the presentation enjoy the talk, which I thought was superb, anyway, here goes .......

Little Waldingfield History Society was delighted to welcome Miriam to the Parish Room, to share her knowledge of the tea trade and its many links to Suffolk.

Growing and manufacturing tea

The story of tea begins in China, where according to legend, in 2737 BC, the Chinese emperor Shen Nung was sitting beneath a tree while his servant boiled drinking water, when some leaves from the tree blew into the water. As a renowned herbalist, Shen Nung tried the infusion his servant had by accident created - the tree was a Camellia Sinensis, and the resulting drink was what we now call tea.

Chinese scholars meeting at a tea party

Tea bush grows only in tropical and subtropical climates, and is cultivated solely for the purpose of its leaves, which are collected as many times per year as tea plant vegetates, or produces new shoots with leaves. In Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Kenya, the south of India and China, summer is all year round; the further north plantations are located the shorter the tea harvesting season is.

Tea is harvested by hand, with only a few young and juicy leaves plus a portion of the stem and the so-called bud or tip (an unexpanded leaf at the end of the shoot); together these are called a "flush", and are the basis of tea production. With two or three leaves it is called "golden flush", but flushes can also be collected with three, four or even five leaves.

Tea leaf picking in China

The first British Tea reference was in a letter by Richard Wickham, who ran an East India Company office in Japan, in 1615 to a merchant in Macao requesting the best sort of chaw. In 1664 the Company placed its first order to import tea into Britain.

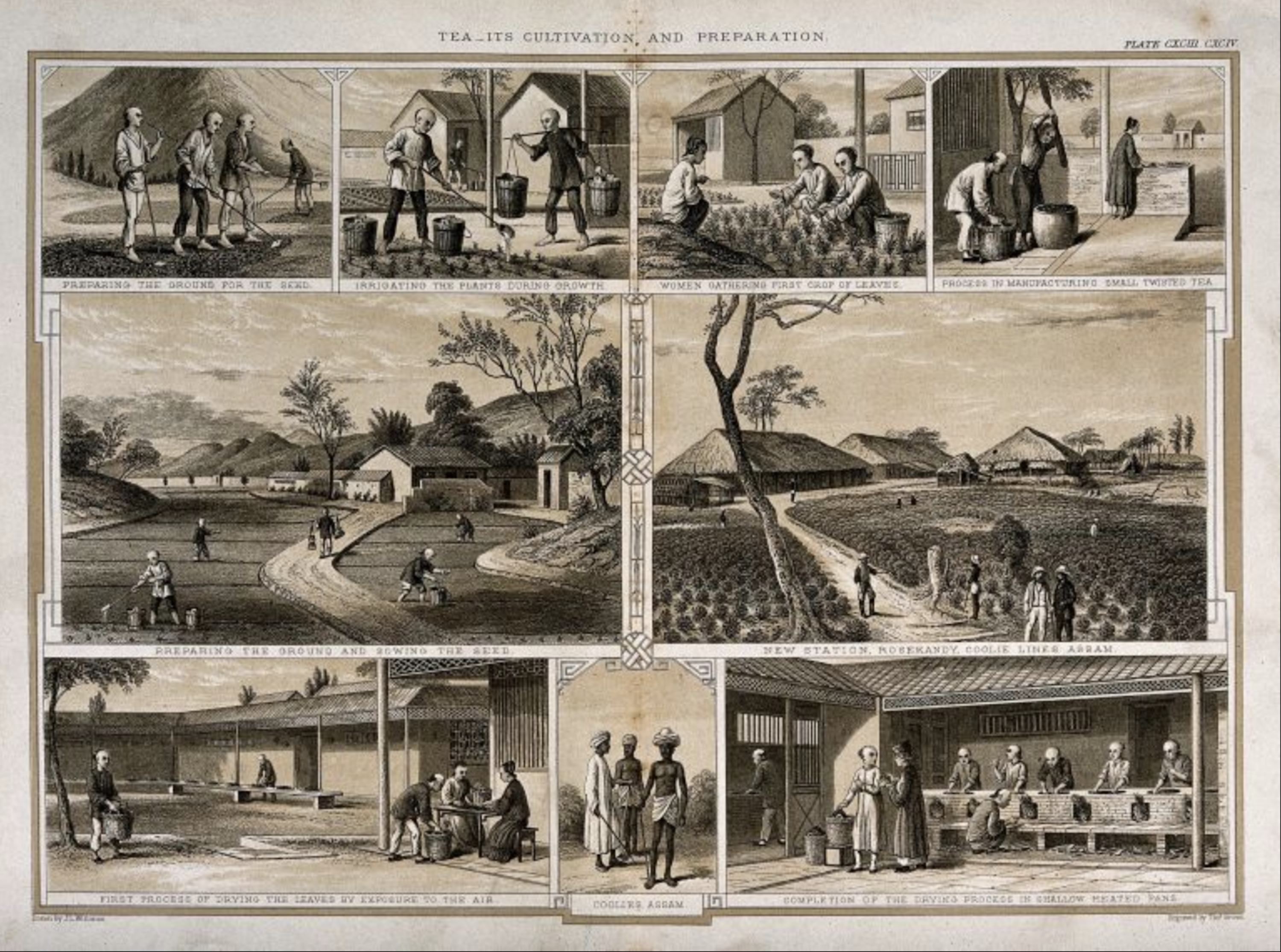

An 1850 British engraving, entitled ‘Tea, its cultivation and preparation’ shows the following stages of the overall process:

- Preparing the ground for the crop.

- Irrigating the plants during growth.

- Women gathering the first crop of leaves.

- Preparing the ground and sowing the seed.

- New Station Assam.

- First process of drying the leaves by exposure to the air.

- Coolies, Assam.

- Completion of the drying process in shallow heated pans.

Tea cultivation and preparation

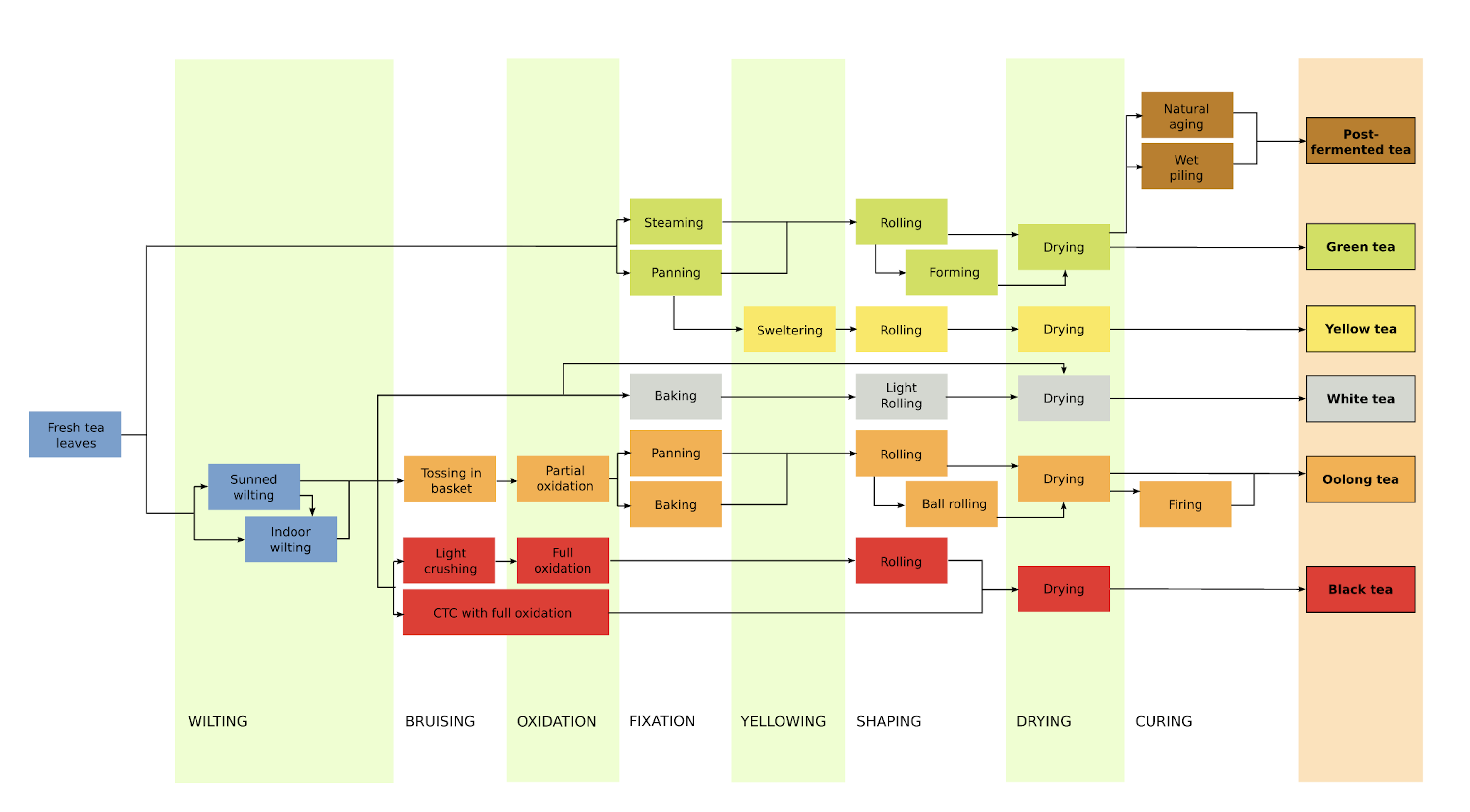

Although each type of tea has a different taste, smell and visual appearance, tea processing for all tea types consists of a very similar set of methods, with only minor variations.

- Plucking: picking the flushes.

- Withering / wilting: leaves wilt as soon as they are picked, and withering removes excess water.

- Disruption: leaves are bruised, or torn, to promote or quicken oxidation.

- Oxidation: to release or transform the tannins.

- Fixation / Kill-green: done to stop leaf oxidation at the required level.

- Sweltering / yellowing: a process unique to yellow teas.

- Rolling / shaping: damp leaves are rolled to further enhance tea taste.

- Drying: done to finish the tea for sale.

- Ageing / curing: not always required, can be used to flavour the tea.

- Sorting: to remove physical impurities (stems, seeds) and classify teas by grade.

- Packing: in airtight containers, usually plywood lined with aluminium foil to keep moisture out.

The above are graphically illustrated by the Wikipedia tea processing diagrammatic image.

Tea leaf processing methods for the six most common types of tea

Arrival in London and port handling

Miriam advised that tea could be stored in any warehouse, but that it was always handled in particular ways, primarily because it was such a valuable commodity and very heavily taxed.

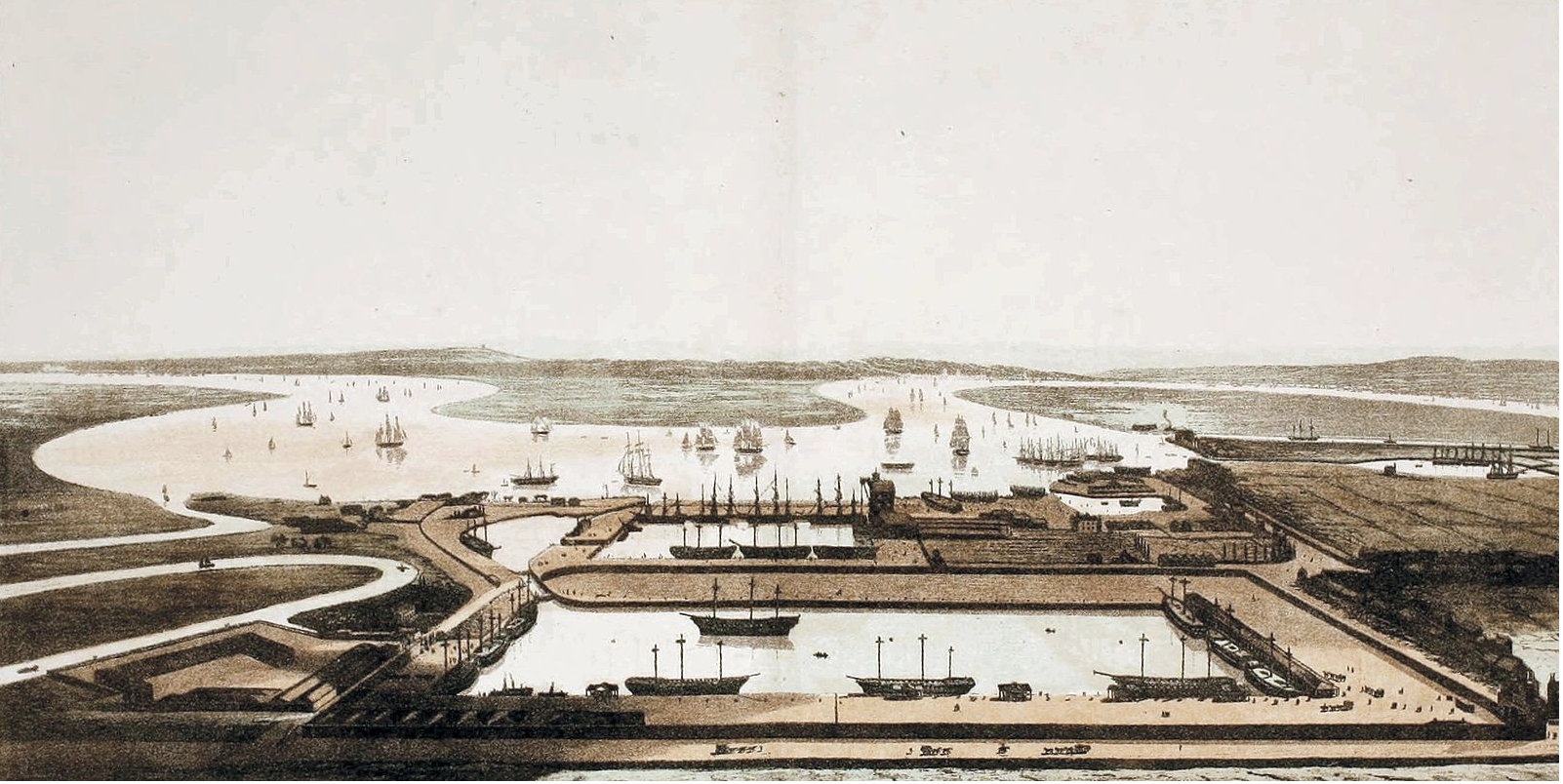

Following the successful creation of the West India Docks, which opened in 1802, an Act of Parliament in 1803 set up the East India Dock Company, promoted by the Honourable East India Company.

East India docks in 1806

The company rapidly became profitable through its trade in commodities such as tea, spices, indigo, silk and Persian carpets, with the tea trade alone being worth some £30 million a year, astonishingly worth some £2.5 billion in today’s money. Tea was dutiable, so was stored in bonded warehouses with the duty to the Crown paid only when removed (for onward sale).

The docks spawned further local industry, with spice merchants and pepper grinders setting up around the dock to process goods, the scale of the overall operations clearly evidenced by the size and opulence of their Head Office and their Cutler Street warehouses.

East India House by Thomas Malton

Hay’s Wharf was just one of a number of wharves lining the Thames in London, used as places whereEast India House by Thomas Malton ships could dock and receive goods and passengers for transport across the country and abroad. During the C19th tea clippers from China brought a high percentage of all the tea consumed in London into Hay’s Wharf. In 1834 the famous clipper races began in China, going down the China sea, across the Indian Ocean, round the Cape of Good Hope, up the Atlantic, past the Azores and into the English Channel. The clippers were then towed up the Thames to London by Tugs, and the first ship to throw its cargo onto the docks was the winner, commanding the highest tea prices.

Tea clipper Flying Spur entering Hay's Whary by Gordon Ellis - Courtesy of A London Inheritance.

By the end of the 20th century Hay’s wharf was substantially renovated, including the infill of the old central dock and conversion into Hay’s Galleria - a mixed use building in the London Borough of Southwark, featuring offices, restaurants, shops, and flats.

Hay's Galleria courtesy Metro Girl

Tea arrived in London packed in tea chests, essentially plywood boxes strengthened with metal edging strips and lined with foil to keep the tea dry. Before distribution could begin, chests were brought from the warehouse and opened, with samples taken from each, for inspection by tea experts. If the quality was OK, the tea was then mixed together, repacked and sealed in the same chests, with some ‘tramping down’ to ensure that all of the tea could fit back into the chests.

The tea chests were now of roughly similar weight and the same consistent quality, and were then stored by grade, as evidenced by various chalk marks on the floor of the tea warehouse.

Tea was sold via quarterly East India Company auctions, with London eventually becoming the tea capital of the world (until the 1990s, when customers could buy direct from teas growers / producers). There were generally many tea brokers and middlemen involved throughout the tea business.

Distribution

Originally this was by smaller boats around the coast, and post the breaking of the East India Company monopoly, mainly by railway, though Typhoo transhipped their tea by canal barge to Birmingham.

Miriam then told us that Suffolk alone consumed some 1,600 chests of tea annually, so with each chest weighing about 84 lbs, this amounted to some 134,400 lbs or 60 tons - quite a lot of tea. Bringing the tea trade in the East full circle, Miriam advised that the port of Felixstowe is now the largest importer of tea into Britain.

Vintage tea chests on Ebay

Tea tax and smuggling

By the 1700s Britain was obsessed with tea, but taxes put it out of reach of most people, with 5 million pounds of tea sold legally but 7 million pounds smuggled! Tea was smuggled from Holland, via the Dutch East India Company; Revenue Officers and Troops vainly tried to control this but mainly failed, hence the famous Smugglers Song:

If you wake at midnight, and hear a horse's feet,

Don't go drawing back the blind, or looking in the street;

Them that ask no questions isn't told a lie.

Watch the wall, my darling, while the Gentlemen go by!

Five and twenty ponies,

Trotting through the dark,

Brandy for the Parson,

Baccy for the Clerk;

Laces for a lady, letters for a spy,

And watch the wall, my darling,

While the Gentlemen go by!

Additional verses follow .......

Miriam then told us of the ‘Hadleigh Gang’, which comprised some 100 smugglers with 120 horses - indicating the scale of the problem - and made reference to Margaret Catchpole (see our May 2018 blog entry). Fights took place on beaches and people were injured and killed; these were desperate characters and times indeed. Tea smuggling only stopped after 1784, when William Pitt reduced tea duty from 120% (this is not a misprint) to 12.5%, which perhaps counter intuitively increased the revenue to the Government.

Selling tea

Originally tea was mostly sold by local grocers and shopkeepers, then later by chain stores and the Coop, and from 1900 by the Home and Colonial Stores.

Because of its cost at the time, tea was sadly adulterated with many substances to make it go further and increase profits, some of which sound decidedly dangerous to your writer:

Prussian Blue: A dark blue pigment produced by oxidation of ferrous ferrocyanide salts!

Indigo: Created from plants native to East Asia, Egypt, India and Peru in antiquity.

Graphite: A mineral composed of stacked sheets of carbon atoms with a hexagonal crystal structure.

Gypsum: Widely mined; a fertilizer and main constituent of plaster, blackboard chalk and drywall.

Soapstone: A type of metamorphic rock composed largely of the magnesium rich mineral talc.

The sale of packed tea via agents, who advertised their wares through local newspapers, ultimately lead to the many tea brands we have today; these agents usually undertook other businesses such as printing, which perhaps explains where some of the adulteration materials came from.

In the C19th tea began to be sold in paper bags / packets, cementing the links between tea selling and printing, with special bags printed to celebrate the visit of foreign dignitaries and royalty. Later in the 1860s Assam (Indian) tea was introduced to Britain via the Assam Tea Company of London.

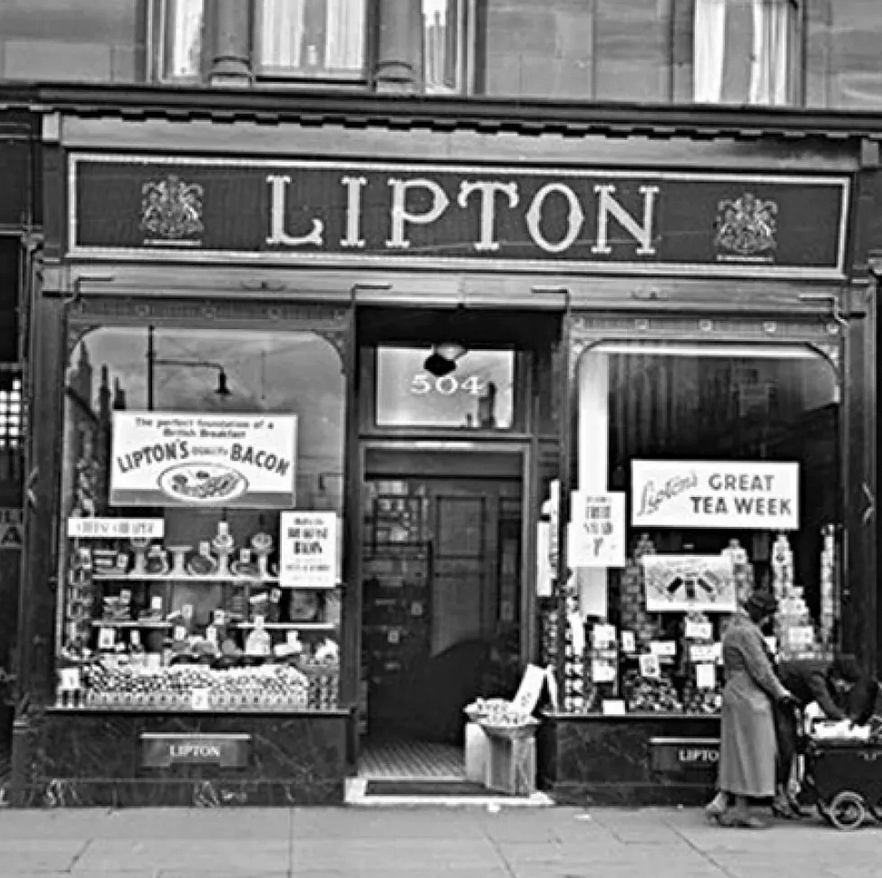

This was later followed by Ceylon tea and then Lipton teas some 20 to 30 years later. Sir Thomas Lipton began by helping his parents run their grocery store in Glasgow, and soon had a number across the city. Tea was one of the products sold, and he soon spotted huge potential, buying his first tea estate in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), reorganising it and introducing an innovative cable car to transport tea leaves more efficiently across the estate.

Liptons first shop, courtesy Unilever

Lipton took self-promotion to a new level, using spectacular publicity stunts at every opportunity. When the first Lipton® grocery store opened in Glasgow in 1871, he celebrated by importing the world’s largest cheese and issuing ‘Lipton Currency Notes’. He established the Thomas J Lipton Co.® tea packaging company in Hoboken, New Jersey; also looking for ways to make packaging and shipping less expensive, instead of arriving in crates, loose tea was packed in multiple weight options. He also cut out the middleman, and was the first to sell loose tea direct to the masses.

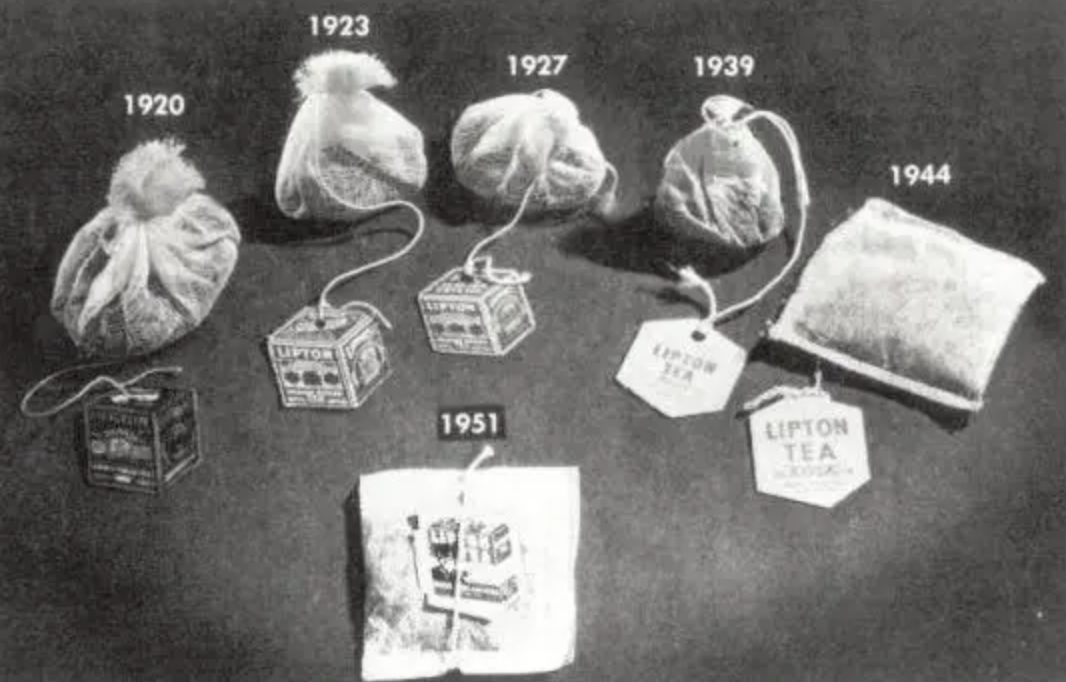

Soon after, tea bags were accidentally discovered by American merchant Thomas Sullivan, who sent tea samples to customers in silk bags, which they then presumed should be placed in water. Thomas Lipton saw the future, and was the first to print brewing instructions on tea bag tags.

Lipton tea bags from 1920 to 1951 courtesy Unilever

Thomas Lipton became incredibly wealthy, and in 1929 he issued his fifth challenge to the Americans for the America’s Cup, commissioning the build of the first J Class (unbelievably expensive) Yacht, signifying the start of a new era in design evolution and racing.

In 1953 World War tea rationing is finally lifted, to great joy, and Tetley Teas then brought their first tea bag to market.

Miriam completed her superbly interesting talk with a selection of images of many tea packets over the years, clearly demonstrating just how popular our national drink really is. All members present had a thoroughly enjoyable time, whilst further thanks must again go to Miriam for donating her speaker fee to charity.

Andy Sheppard 19th October 2021